he drive from Ranchi to Hazaribagh in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand is only 65 miles, but it takes nearly three hours. We swerve to avoid schoolchildren chatting with friends and meandering down the highway, honk at cows to get out of the way, and accelerate past pickups reconfigured as makeshift transport vehicles overflowing with workers. Men in sandals push bicycles overloaded with bags of coal down the highway, while on the back roads close to Hazaribagh, women carry buckets of the stuff on their heads.

Coal is what brought me to Jharkhand, one of India?s poorest and most polluted states. The pedestrian colliers, illegal miners trying to make ends meet, are just the start. All along the route to our destination, the Topa Open Coal Mine, a caravan of large, colorful trucks filled to the brim with coal barrel toward us in the opposite lane. When we finally reach the mine, I see the source of it all: an explosion has blasted through a wall of rock, opening access to new tranches of coal to feed the country?s fast-growing power and industrial needs. says JK John, the senior mining supervisor on site employed by a subsidiary of the state-owned Coal India Ltd.: ?Here, coal is in demand.?

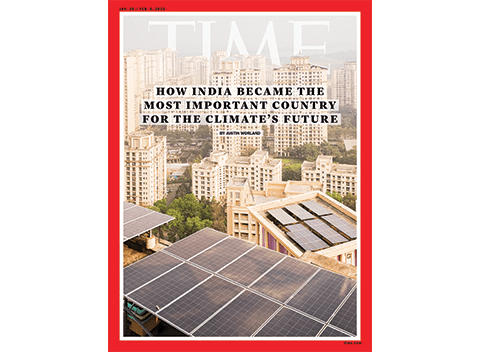

Two flights and more than 900 miles away, the northwestern state of Rajasthan is a world apart. Along a smoothly paved highway from the Jaisalmer airport, wind turbines dot the landscape as far as the eye can see. Farther from the town?s center, we approach a field of solar panels, comprising a 300-MW power plant opened in 2021 by the Indian company ReNew, providing electricity for the growing population of the state of Maharashtra, home to Mumbai. Even as the region expands its renewable-energy industry, the atmosphere remains clean and pleasant enough to support a thriving tourist trade.

Jharkhand and Rajasthan, so different in appearance, are being shaped by the same fundamental force: India is growing so rapidly that its energy demand is effectively insatiable. But the two states present starkly different answers to that demand. Historically, fossil fuels from places like Jharkhand powered industrialization. But today, with climate concerns rising, many experts are calling for India to ditch coal as soon as possible and embrace the green-energy model so prevalent in Rajasthan.

Much rides on which approach dominates India?s energy future. In the three decades since reducing emissions became a discussion point on the global stage, analysts have portrayed the U.S., China, and Europe as the most critical targets for cutting pollution. But as the curve finally begins to bend in those places, it?s become clear that India will soon be the most important country in the climate change effort.

In December, I spent 10 days in India, visiting coal communities, touring renewable-energy sites, and talking with leaders in the country?s political and financial hubs to understand India?s approach to the energy transition. The picture that emerged is of a government following an approach uncharted for a country of its scale: pursue green technologies in the midst of industrialization while leaving the fate of coal to the market. ?India, as a responsible global citizen, is willing to make the bet that it can satisfy the aspiration for higher living standards, while pursuing a quite different energy strategy from any large country before,? says Suman Bery, who leads NITI Aayog, the Indian government?s economic policy-making agency. India, Bery says, will pursue clean energy while seeking a ?balance between energy access and affordability, energy security, and environmental considerations.?

Where that balance is struck could tip the climate scales worldwide. India contributes 7% of the emissions that cause global warming today, a percentage that will expand alongside its economy. This growth will help determine whether?and by how far?the world blows past the goal of keeping global temperatures from rising more than the Paris Agreement target of 1.5℃. Equally important, India?s approach is being watched elsewhere. If it can use low-carbon development to bring prosperity to its 1.4 billion people, others will follow. Failure could lead to a retrenchment into fossil fuels across the Global South.

What the Global North does matters too. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates India needs $1.4 trillion in additional investment in coming decades to align its energy system with global climate targets; that will very likely require reforms at international lenders like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to facilitate the flow of money. The best outcome, observers say, is one where India gets the help it needs to make the best choice for everyone. ?India has to do it for itself,? says Rachel Kyte, the dean of the Fletcher School of international affairs at Tufts University. ?And India needs to do it for the world.?